Charlie Munger Should Never Have Gone To Santa Barbara

Dear Magicians,

I have a confession.

I’ve spent most of my career looking for role models. The right people to emulate. The researchers who seemed to have it all figured out.

But I was looking in the wrong direction.

The Problem With Role Models

Here’s what no one tells you in graduate school: good role models are rare. Exceptionally rare. For every Nobel laureate whose career validates the system, there are hundreds of researchers who burned out. Who stagnated. Who quietly gave up.

This isn’t cynicism. It’s statistics. And yet we’re told to study the winners. Reverse-engineer their habits. Copy their approach.

But that’s survivorship bias. We’re building a theory of success using only the survivors. In physics, we’d never accept this. We’d demand the null results. The failed experiments.

So why do we ignore them in our careers?

Invert the Question

Charlie Munger had it right: “Invert, always invert.” Don’t ask, “How do I succeed?” Ask, “How do I avoid failure?”

This isn’t semantic. It’s fundamental. In thermodynamics, we learn more from entropy than from order. In astronomy, dark matter—what we can’t see—revolutionized cosmology.

The same applies here. Anti-models are everywhere. Failed careers. Bitter colleagues. Researchers who started brilliant and ended irrelevant. They’re not aberrations. They’re data.

What Anti-Models Reveal

Think about dating advice. You could study Brad Pitt. Learn his moves. Adopt his confidence. But his experience is atypical. Statistically meaningless.

The real lessons? They come from failure. From struggle. From people who made mistakes and learned what not to do. Academia works the same way.

The most valuable information isn’t in the success stories. It’s in the cautionary tales. The negative space.

How to Use This

First: observe. Systematically. Look at colleagues whose careers stalled. What patterns repeat? Inability to adapt? Overcommitment to administration? Reluctance to collaborate? Write it down. These are signals.

Second: run premortems, not postmortems. Before any major decision, ask: “If this fails, what would be the most likely cause?” You’ll see blind spots you’d otherwise miss.

Third: study the unhappy. Not the content professors. The dissatisfied ones. What makes them miserable? Structural factors? Bad habits? Wrong priorities? Then avoid those things. Ruthlessly.

A Warning

Munger also said he wanted to know where he’d die so he could never go there. He died in Santa Barbara. Where he lived.

The point? No framework is perfect. No inversion guarantees success. But it improves your odds. Dramatically.

The Physics of Failure

In statistical mechanics, disorder is the default. Entropy always increases. The number of ways to fail vastly outnumbers the ways to succeed.

This isn’t pessimism. It’s reality. Academic careers work the same way. Burnout, irrelevance, bitterness—these are the high-probability states. Fulfillment and impact? Those are rare configurations.

So our job isn’t to chase some idealized trajectory. It’s to systematically avoid the most common failure modes. Prioritize adaptability. Value process over outcomes. Recognize when the institution itself is the problem. This is meta-cognitive work. It requires honesty.

Make It Practical

Start a journal. Private. Candid. Document the behaviors you see—in others, in yourself—that lead to negative outcomes. Patterns will emerge.

Ask trusted colleagues: “What am I doing that might be quietly sabotaging me?” You won’t see it yourself. The anti-model rarely does.

Design small experiments. Invert your usual approach. Observe what happens. And cultivate humility. Today’s anti-model might be tomorrow’s necessity. The landscape shifts.

The Real Insight

Studying anti-models isn’t about cynicism. It isn’t about schadenfreude. It’s about intellectual rigor.

In physics, the universe is shaped as much by absence as by presence. Dark energy. Dark matter. The voids between galaxies. Your career is the same.

So next time you’re tempted to find another role model, stop. Ask instead: What are the anti-models around me? In my field? In my own habits? What can I learn from the negative space?

The answers won’t be comfortable. But they’ll be true.

What’s your Santa Barbara? And are you already living there?

Until next time, have a M.A.G.I.C. Week,

Brian

Dear Magicians,

I just got back from my third trip from San Diego to the East Coast in as many weeks. This time, I was in New York City. Maybe for the last time in a long while. The city felt different—edgier, more uncertain, as if the very air was charged with the anxiety of what’s coming next. I stayed on Fifth Avenue, surrounded by the storied facades of publishing houses that once defined literary ambition. It’s impossible not to remember the first time I walked these streets as a newly minted author, contract in hand, head full of the mythology of publishing for my first book, Losing the Nobel Prize.

In 2017, Ind thought I knew what I was walking into—the grand lobbies, the marble, the sense of entering a cathedral of ideas. I imagined myself as a character in the golden age of publishing—editors in tailored suits, writers with ink-stained fingers, the whole city humming with the energy of creation. That’s the story we’re sold, isn’t it? That prestige is substance that the correct address and the right logo on your book spine are a kind of intellectual validation.

Wrong.

The reality was a little different. I remember taking the elevator up to the fiftieth floor, rehearsing my pitch, my gratitude, my best impression of someone who belonged. I asked a security guard for directions to my editor’s office—Jeff Shreve, associate acquiring editor at one of the most respected houses in the world, W.W. Norton. The helpful guard pointed me thusly: “Go around two corners and hang a left. That’s his office”.

I followed his instructions, only to find myself staring at a janitor’s closet. This can’t be right. I thought I’d made a mistake. I hadn’t.

Jeff’s office was, in fact, the janitor’s closet. Broom, mop, cleaning supplies, and all. This was the office of a gatekeeper to my literary legitimacy. The symbolism was almost too on-the-nose. Substance over size? Or just the slow decay of an institution that still trades on its reputation long after the reality has changed?

Within months, Jeff left the firm. He was too smart to stay. He struck out on his own, independent, unencumbered by the trappings of prestige. I was left with a question that still haunts me: What, exactly, are we buying when we chase institutional validation? Is it access? Is it credibility? Or is it just the comfort of a story we want to believe?

You know this feeling. We all do.

The Bonfire of the Gatekeepers

When my first book, Losing the Nobel Prize, finally found a home, it was after nineteen rejections. One publisher said yes. I was elated—briefly. The book sold over 20,000 copies, earned hundreds of reviews, and, most importantly, found its way into the hands of readers who left thoughtful, sometimes life-changing feedback. It changed lives, mine and my readers. But the process left me with a persistent sense of disillusionment.

Here’s what nobody tells you: The most significant benefit of traditional publishing isn’t the prestige, the marketing muscle, or even the editorial guidance. It’s the legal department. I learned this the hard way.

I fought for my title—Losing the Nobel Prize—and won. It’s not a forgone conclusion that a first-time author gets to choose their own title, I would later learn. But I compromised on the cover. The publisher chose a photograph: BICEP2 at the South Pole, under a sky alive with aurora. Beautiful, evocative, and, as it turned out, radioactive.

But the publisher’s legal team discovered they’d bought rights from someone who didn’t own them. The real owner wanted the cover pulled.

Devastating? At first, yes. The publisher had to halt production, recall books, and commission a new cover. For a first-time author, this should have been a career-ending fiasco.

But here’s the twist: Embedded in my contract was a clause I’d barely noticed. Any new edition—paperback, audiobook, revised hardcover—required a new launch, new publicity, and a new book tour. The legal disaster forced a second release, a second round of attention, a second chance. Sales spiked. I landed on major podcasts, including Ben Shapiro’s Sunday Special. The new cover photo, taken by a scientist who actually wintered at the South Pole, was even better.

The Physics of Prestige

There’s a physics to institutional prestige. Like potential energy, it’s stored in the architecture, the rituals, the stories we tell about who gets to belong. But when you open the box—Schrödinger’s publisher, if you will—you find the cat is both alive and dead. The prestige is real, but hollow. The gatekeepers are sharing offices with mops.

Think about that.

We’re trained to believe that the right imprimatur is a kind of career insurance. That if you just get the right logo on your CV, the right publisher on your book, the right journal for your paper, you’ll be safe. But safety is an illusion. The real value is in the work itself—and in your ability to metabolize setbacks into momentum.

After that experience, I chose to self-publish my next three books. Not because I wanted to be a rebel, but because I’d seen behind the curtain. The machinery of prestige is just that—machinery. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it breaks down. But it’s never a substitute for substance.

What Are You Walking Past?

I used to walk past those grand Mad Men-appointed publisher lobbies and feel envy. Now I see them for what they are: monuments to a past that no longer exists. The real work happens in the margins, in the closets, in the places nobody thinks to look. The real value is in the conversations with readers, the honest reviews, the moments when someone tells you your book changed the way they see the world.

Regret has a structure. It’s information. The question is whether you’re willing to use it.

So, what are you walking past? What stories about prestige, legitimacy, or safety are you still buying? What would you do differently if you stopped waiting for permission?

I’m not saying the answer is always self-publishing, or quitting your job, or burning down the system. But I am saying this: The institutions you revere are more fragile, more arbitrary, and more human than you think. And sometimes their foibles do you a real favor.

Until next time, have a M.A.G.I.C. Week,

Brian

Appearance

In this video, I talk about the origins of the universe, the Big Bang, cosmic microwave background radiation, cosmology and cosmic inflation.

Genius

Is there a book you have ever thought – “I wish I didn’t read it so I could read it for the first time.”

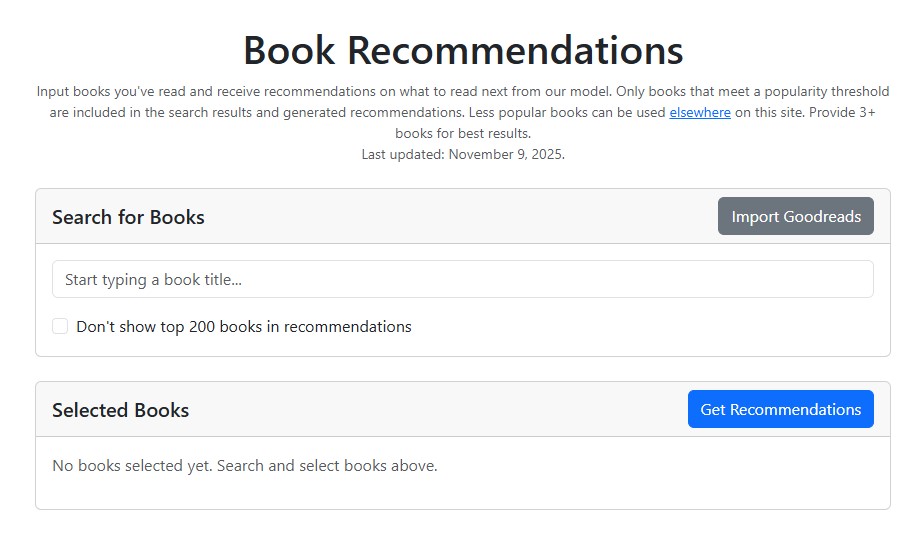

Check out https://book.sv/similar?id=56498636

Image

Conversation

What would happen if Einstein’s funding was cut just before he made E=mc². I took a walk at UCLA with the Mozart of Math, Terry Tao, to uncover how politics is destabilizing science, why math is our most important infrastructure, and what he does next.

Sponsored

When Chris Hadfield told me astronauts live and die by checklists, I smiled—because so do I.

Just, in my case, the stakes are a little lower:

Quantum mechanics lecture? Check.

Podcast prep? Check.

Orthodontist rubber bands? Check.

For years, I’ve used Todoist to keep my personal chaos and my team’s projects aligned. Unlike bloated project management tools that feel like a second job, Todoist is lightweight, powerful, and actually fun to use. It keeps everyone on track without endless status meetings or confusing dashboards.

If you run a small or medium team, Todoist Business is the mission control you need. And as a subscriber of Into the Impossible, you get 30 days free.

Try it here: https://get.todoist.io/ukirup

Checklists keep astronauts alive. Todoist keeps the rest of us productive.

Upcoming Episode

Anil Ananthaswamy will be on The INTO THE IMPOSSIBLE Podcast soon.

He’s the award-winning science journalist who wrote Through Two Doors at Once, an intellectual detective story tracking how the double-slit experiment—that deceptively simple setup where particles behave impossibly as both waves and particles—has haunted physics for two centuries and continues forcing us to question whether reality exists before we observe it, whether the universe splits with each measurement, and if quantum mechanics demands we abandon our intuitions about space and time itself.

What would you ask someone who’s traveled the world interviewing the physicists conducting cutting-edge variations of this “most fundamental of quantum experiments” about what their results reveal regarding the nature of reality—submit your questions here.